I am humbled by the warm reception that the Scalawag article has received. Thank you for the many kind words. For those who have read it and would like to learn more, I offer a partial list of sources. For either space or aesthetic reasons, the footnotes in the final draft were omitted for publication.

I first learned about the existence of the Patriots of North Carolina from an exceptional book that tells the story of the North Carolina Fund, a pioneering anti-poverty initiative in the 1960s. Robert R. Korstad & James L. Leloudis, To Right These Wrongs: The North Carolina Fund and the Battle to End Poverty and Inequality in 1960s America, UNC Press (2010).

The quote from the President of the Patriots of NC came from: W. C. George, The Biology of the Race Problem, A Report of the Commission of the Governor of Alabama (1962). See also George Lewis, “Scientific Certainty”: Wesley Critz George, Racial Science and Organized White Resistance in North Carolina, 1954-1962,” Journal of American Studies, 38:2 (2004).

The term “Progressive Plutocracy” was coined by V. O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics in State and Nation A.A. Knopf (1949); Fellow Scalawag contributor Prof. William Chafe modified this formulation, dubbing North Carolina’s politics a “progressive mystique” in Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom, Oxford University Press (1981). Prof. Chafe’s book was an invaluable source for understanding the Civil Rights movement in Greensboro and the context in which the Patriots were founded.

Information about the Pearsall Plan and North Carolina’s success at holding off integration came largely from the following sources and other documents in the W. C. George Papers at the Southern Historical Collection:

• The Pearsall Plan to Save Our Schools, educational brochure prepare by the Advisory Committee on Education [thePearsall Committee] (1956)

• William W. Taylor, Jr., My First Ninety Years (2002) [unpublished memoir, provided by his son, William W. Taylor, III; William Taylor, Jr. staffed the Pearsall Committee with his future law partner, Tom Ellis]

• I was reminded of Gov. Hodges’s attempt to enlist African American support for what he called “voluntary segregation,” urging Black parents not to attempt and integrate White schools by Anders Walker, The Ghost of Jim Crow: How Southern Moderates Used Brown v. Board of Education to Stall Civil Rights, Oxford U Press (2009).

• Davison Douglas, The Rhetoric of Moderation: Desegregating the South During the Decade After Brown, 89 Nw. U. L. Rev. 92 (1994). In 1964, less than one percent of North Carolina’s African American pupils attended school with Whites.

• John Drescher, Triumph of Good Will: how Terry Sanford Beat a Champion of Segregation and Reshaped the South, University press of Mississippi (2000).

These books (and article) provide a great overview of how massive resistance to the Brown decision developed across the South:

• Neil R. McMillen, The Citizens’ Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction, U of Illinois Press (1971)

• Numan V. Bartley, The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South During the 1950’s, LSU Press (1969)

• Francis M. Wilhoit, The Politics of Massive Resistance, George Braziller (1973)

• Sarah H. Brown, The Role of Elite Leadership in the Southern Defense of Segregation, 1954-1964, Journal of Southern History, Vol. 77, No. 4 (Nov. 2011)

Information about efforts to enforce desegregation orders, the state of my hometown schools, and how racial discrimination is at the root of housing patterns that are still with us today was found here:

• Nikole Hannah-Jones, Lack of Order: The Erosion of a Once-Great Force for Integration, ProPublica (May 2014)

• John Hinton, Winston-Salem Practiced Jim Crow when Winston and Salem were Consolidated,” Winston-Salem Journal (June 30, 2013). In discussing residential segregation, it is important to note that it cannot be ascribed to unfettered choice. In my hometown of Winston-Salem, segregation was written into the zoning code in 1912 and restrictive covenants, prohibiting the sale of real estate to people of color, were commonplace. For decades thereafter, federal housing policy reinforced such segregation, with FHA loans going overwhelmingly to White homeowners in neighborhoods that were inaccessible to African Americans. Though these policies have not been in force since the late 1960s, racially segregated neighborhoods, with vast gulfs between home values, remain.

• For data about Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, I turned to Jennifer B. Ayscue et al, Segregation Again: North Carolina’s Transition from Leading Desegregation Then to Accepting Segregation Now, Civil Rights Project at UCLA (May 14, 2014) (Winston-Salem Metro Summary [pdf])

• Ta-Nehisi Coates’s writing has been critical in unearthing the larger story of how federal and state policy shaped the structural disadvantage in housing policy for African Americans while simultaneously creating a path to middle class wealth accumulation for Whites. See Coates, The Case for Reparations, the Atlantic (June 2014)

• I found extremely helpful insights into the nature of locked-in advantages for Whites that lingers today from the Jim Crow era from Daria Roithmayr, Reproducing Racism, NYU Press (2014) (h/t Jed Purdy)

For background into Chief Justice Roberts’ ideological and policy positions in the Reagan White House, see Jeffrey Toobin, No More Mr. Nice Guy: The Supreme Court’s Stealth Hard-Liner, New Yorker (May 25, 2009) and Testimony of Wade Henderson, Executive Director of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, before the Senate Judiciary Committee (Sept. 15, 2005)

There is a brisk summary of how Tom Ellis and Jesse Helms’s political team engineered Ronald Reagan’s improbable victory over the incumbent President Ford in the North Carolina’s 1976 Republican Primary in Rick Perlstein’s Invisible Bridge, Simon & Schuster (2014). Jesse Helms built his brand of dog-whistle conservative politics as a commentator on WRAL-TV, a station owned by A. J. Fletcher, law partner in the 1950s to pro-segregation gubernatorial candidate and frequent Patriots of NC speaker I. Beverly Lake, Sr.

For more on the idea that Jim Crow segregation played an instrumental role in the southern labor system, see Jason Morgan Ward, Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936-1965, UNC Press (2014) (noting that southern industrialists began to fight New Deal policies in order to maintain the “competitive advantage that cheap black labor provided” and because they believed that a “segregated, low-wage labor system provided the South a path to modernization and prosperity.”). See also David Cunningham, Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan, Oxford University Press (2012).

The Southern States Industrial Council was a powerful coalition of conservative businessmen that fought hard to maintain segregation and the low-wage southern labor system with ties to the Dixiecrats and the Federation for Constitutional Government. North Carolina’s own David Clark, brother of Patriots-founder John Clark, published the Southern Textile Bulletin. David Clark used the specter of Blacks and Whites working together in the mills to fire up working class opposition to liberal politicians, most notably Frank Porter Graham in the infamous primary run-off with Willis Smith in 1950.

Examples of the dominant myth that Black involvement in civic and political life in Reconstruction and during the Fusion era lead to corruption are not hard to find: “[the] brief rule [of ‘Carpet-baggers and their Negro allies’] was characterized by inefficiency, extravagance, violence, and unblushing corruption.” Hugh Lefler and Albert Newsome, North Carolina, UNC Press (1953); see also R.D.W. Conner and Clarence Poe, The Life and Speeches of Charles Brantley Aycock, Doubleday, Page & Company (1912). Gov. Aycock left no doubt about the central role of White Supremacy and ending what he deemed the corrupt “Negro rule” during the Fusion era in working to reassert the dominance of the Whites-only Democratic Party.

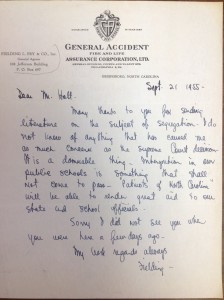

The first letter that I found from Fielding in the archives (Erwin A. Holt Papers, Southern Historical Collection)